With Roe likely in its final days, experts say reporters should sharpen focus on abortion as a health issue

Photo by Erica TricaricoSophie Novack (on the left) and Crystal S. Berry-Roberts, M.D. (on the right)

Pregnancy is a medical condition and abortion is an intervention for it, so journalists writing about the topic should take the same approach they would when writing about cancer, diabetes, and other conditions and treatments: focus on mortality risks, patients’ rights to care and bodily autonomy.

Reporters should also step up their game to explain what the medical community has known for decades: that abortion is a safe health care procedure.

These were among the topics covered by women’s reproductive health experts who participated in a round table discussion moderated by Brenda Goodman of CNN Health, about abortion on Saturday, April 30, at Health Journalism 2022 in Austin. The conversation took place two days before what appeared to be a leak of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Roe v. Wade was published by Politico. The opinion would overturn abortion protection under Roe v. Wade.

Check out the full transcript of the round table discussion.

The speakers at the “Women’s reproductive health in a post-Roe world” round table included Crystal S. Berry-Roberts, M.D., an obstetrician and gynecologist in Austin; Lisa Harris, M.D. Ph.D., an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan; Sonja Miller, interim managing director for Whole Woman’s Health Alliance; and Sophie Novack, an independent journalist who has reported on the implications of Texas laws restricting abortions.

During the one-hour conversation, panelists emphasized the emotional toll abortion restrictions under Senate Bill 8 — more commonly known as SB8 — are taking on women who fear they will be criminally charged for getting an abortion, as well as on Texas doctors, nurses, physician assistants and other medical personnel who must now worry they are breaking laws when counseling patients to end pregnancies. They also discussed the vague language used to define medical exceptions and the implications of restrictive laws on self-managed abortions.

The featured experts are among many health professionals concerned about the negative impact abortion bans will have on women’s health, and particularly, that legislation that restricts or outlaws induced abortions in any stage of pregnancy may result in an increase in the country’s already troubling maternal mortality rate among women of color.

Considering that most pregnant women won’t know for at least 10 weeks into their pregnancy whether there is something wrong with the fetus, Dr. Berry-Roberts said that the six-week limitation in the Texas law is an “unrealistic timeline” considering the implications of a lifelong decision that causes great stress in women’s lives and leaves them feeling depressed for a long time.

“I’ve seen it cause harm,” said Berry-Roberts, who does not perform elective abortions. “When I have to now choose my words more technically and strategically, I may be doing harm. Because I may be impacting how I am educating that patient post S.B. 8 compared to how I would have educated her a year ago.”

Since the Texas law went into effect in September 2021, Berry-Roberts said she’s had to consider whether seeing patients who may want an induced abortion may put her at risk of being sued because she talks to them about their options. She also said that the current laws and the divisive political discourse about abortion is intensifying the stigma associated with abortion, making it harder for women to talk candidly about their pregnancy with their physicians.

“I have patients who have had abortions for various reasons two, three years ago, 10 years ago. And it is still a point of ‘please don’t bring it up,’” Berry-Roberts said.

Although abortion is considered health care, Novack, who has reported extensively about the topic, said she’s noticed that “coverage of it is siloed from other areas of reproductive health care.” Journalists, she said, should think about abortion through the lens of health care access, and include context on uninsured rates, teen pregnancy trends, and state funding for family planning services, among other information that help readers understand how restrictions affect the overall, long-term health of women.

Reporters were also encouraged to address issues related to health equity. Dr. Harris, a practicing obstetrician and gynecologist in Michigan, encouraged journalists to report on abortion through the lens of health equity, and consider what allows some women to more easily travel to access abortion services. In looking at disparities in access, Dr. Harris said reporters should shed light on the state of maternal medical care in rural and urban settings; she’s among physicians who wonder whether the country has enough delivery wards to accommodate the projected jump in births that may result from current and future restrictions on abortion care.

Miller urged reporters not to perpetuate the stigma associated with abortion and cautioned against interviewing people who support outlawing the procedure and spread misinformation about the procedure to further their cause. “I would challenge you to think of the pro-abortion side as inherently balanced,” said Miller. “Because as we sit here in a pro-abortion stance and lens, we are inherently asking for every person to have bodily autonomy. We are asking for all people to be treated equally.”

Below are topics you may want to address in your stories, including some that Berry-Roberts, Miller, and Harris touched on during the event. You’ll also find resources that may help you provide context as you continue to write about abortion and access restrictions.

1. Carrying a baby to term is riskier than having an abortion. Pregnancy complications are common, even among women who don’t have pre-existing medical conditions that may make them more vulnerable and range from mild to severe. Among them are anemia, depression and anxiety, high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, and sexually transmitted infections that may be problematic for the mother and child during pregnancy and delivery. Some medications used to treat health problems during pregnancy or stopping medications for existing conditions may be more harmful to the mother than the pregnancy risks.

Research going back at least two decades has shown that serious complications (e.g., blood clots, heavy bleeding, infection and injury to the uterus and other organs) from abortions are rare; the risk of death during childbirth is much greater than death from abortion. In a 2012 study, scientists said their analysis showed that risk of death during childbirth was 14 times greater than death associated with an abortion procedure.

Mortality resulting from abortion is also exceedingly rare. A 2014 analysis of 10 years of data that looked at mortality of induced pregnancy terminations, dental procedures, outpatient plastic surgeries and leisure activities in the U.S., revealed that the induced abortion mortality rate was at least as low as the one associated with plastic surgeries at accredited or licensed ambulatory surgical facilities.

2. Teens are more likely than women in their 20s and 30s to develop pregnancy-related high blood pressure and pre-eclampsia. Some of the states with the toughest abortion restrictions in the country also have the highest teen pregnancy rates in the U.S. They are mostly in the South, and include Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. Texas also has a high rate of repeat teen pregnancies.

Although the teenage pregnancy rate has declined significantly since reaching a record high in the early 1990s, declines haven’t been as large among some racial and ethnic groups. The latest birth data from the National Centers for Health Statistics shows that the pregnancy rate in adolescents 15-19 dropped:

- 5% for non-Hispanic Black teens

- 7% for Hispanic teens

- 9% for non-Hispanic white teens

- 12% for non-Hispanic Native American and Alaska Native teens

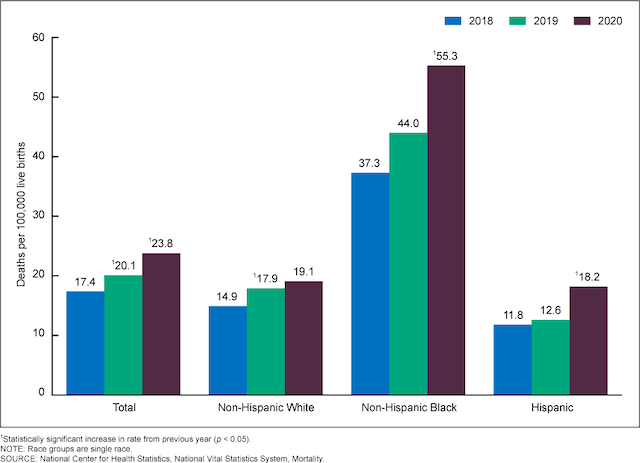

3. The U.S. maternal mortality rate increased between 2018 and 2020, the most recent year for which there is data. Banning abortion in the U.S. may lead to a significant increase in maternal mortality, especially for non-Hispanic Black women.

According to a 2020 report from The Commonwealth Fund, the U.S. had the highest maternal mortality rate among 11 developed countries, including Canada, France, Sweden and the United Kingdom. That 2018 analysis also showed that college-educated non-Hispanic Black women had a significantly greater risk of maternal death compared with non-Hispanic white women and Hispanic American women who don’t have a high school education.

In the most recent maternal mortality report from the National Center for Health Statistics, the data show that the death rate is among non-Hispanic Black women — 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births — was almost three times that of non-Hispanic white women and more than three times that of Hispanic women of any race.

Using three-year data on induced abortions and applying pregnancy-related mortality ratios, a recent study estimated the effects outlawing induced abortion in the U.S. The findings suggest that pregnancy-related deaths would increase even if women who want to terminate their pregnancies resort to unsafe methods to end them. And the estimates show the increase in the pregnancy-related death rate would be most significant among non-Hispanic Black women, Hispanic women of any race and women of other races and ethnicities.

In the first year following the ban, for example, the death rate among non-Hispanic Black women would increase by 12%; in the years that followed, 33%. The annual rate of lifetime risk of maternal death among non-Hispanic Black women in the years after the ban is 1 in 1,000, compared to 1 in 1,300 in the years before the ban.

4. The restrictions may bring legal ramifications for women who have spontaneous abortions and who perform self-managed abortions in the privacy of their homes. These were issues that were brought up by Harris during the round table. The physician said that there’s no way for doctors to distinguish from a pregnancy loss due to a miscarriage or an induced abortion and wondered whether women could be criminally charged for hurting a fetus if they have an unintended pregnancy loss. Although research shows self-managed abortions can be performed safely, Harris said worries that women who go that route to end their pregnancy may be charged for fetal harm and be prosecuted. For more context on that, Harris suggested reporters reach out to the nonprofit National Advocates for Pregnant Women.

The recent case of a woman in Texas illustrates the potential legal consequences some women could face. Although the charge against Lizelle Herrera was later dropped by the district attorney, she was charged by a grand jury for “the death of an individual by self-induced abortion.”